Recently in a Flawed Situational Awareness class we were discussing how situational awareness serves as the foundation for good decision making. Granted, a person does not need strong situational awareness to make a good decision.

When a good decision is made after a person’s situational awareness has eroded, that would be called luck. [tweet this] And it is the goal of this blog and all our live events to help responders avoid making decisions on the foundation of luck.

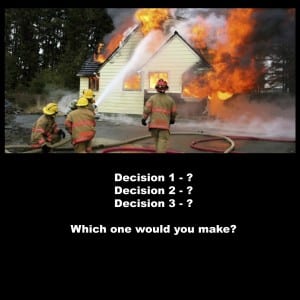

In this contribution, I would like to discuss the decision making of the first-arriving officer at a residential dwelling fire.

Decision Choices

The first arriving officer always has choices on which actions to take (or not take) when arriving on the scene of a working residential dwelling fire. In my simple evaluation of this topic, I am going to discuss three decision choices. Arguably, however, I suppose the decision choices could be endless depending on how many variables you want to consider. But here, I am going to simplify the decision making process down to three.

Decision Choice #1: Following a size-up of the situation (which includes gathering the information that forms situational awareness) the officer decides to establish a “working command” and make entry with the crew. Most often, the mission will be fire suppression and/or search and rescue.

Decision Choice #2: Following a size-up of the situation, the officer decides to establish a fixed command position on the exterior and send the crew in (without the officer) to perform tasks (again, most often related to fire suppression and/or search and rescue).

Decision Choice #3: Following a size-up of the situation, the officer decides to deny entry of the crew and fight the fire from that exterior position. (Note: Merely suggesting this as an option will be enough to have my name smeared on some social media feeds.)

Which is best?

The sad truth is, only the officer who is on the scene, in the moment, gathering the information and assessing the conditions can determine which decision choice is the best. In the fire service, we tend to judge the quality of a decision based on the outcome. [tweet this]

The sad truth is, only the officer who is on the scene, in the moment, gathering the information and assessing the conditions can determine which decision choice is the best. In the fire service, we tend to judge the quality of a decision based on the outcome. [tweet this]

If the outcome is good, the officer will be lauded as a competent commander who made the right call. If the outcome is bad (and any of the three decision choices listed above can result in a bad outcome) the officer stands to be chastised and criticized for not doing one of the two unselected choices. Thus, the first-in officer is in a damned if you do and damned if you don’t situation. [tweet this] Only the outcome will determine if praise or criticism is heaped upon the officer.

Oftentimes the criticism an officer receives for a flawed decision comes from someone who wasn’t even at the scene. [tweet this] How is that person to know the conditions the officer faced in the moment? What information that officer had (or didn’t have)? What intuitive gut-feelings the officer was experiencing that contributed to the decision? Seek first to understand before throwing your judgment and criticism. [tweet this]

This is why you will never see me criticize responders following a event where responders get hurt or killed. I wasn’t there. So I don’t judge. When someone sends me a link to a story or a video, I may share the story or the video… but the most you’ll ever hear me say is something to the effect that situational awareness matters.

Teaching Decision Making

One thing that I have noticed over and over again while observing live fire training scenarios is that many instructors don’t teach (and students don’t practice) the process of decision making during training.

In fact, oftentimes in training the decisions of what to do and how to do it are made by the instructors, not the participants. I suppose there is something to be said about time management and how expeditiously a hands-on evolution can be performed if the students don’t have to think about their actions.

In fact, oftentimes in training the decisions of what to do and how to do it are made by the instructors, not the participants. I suppose there is something to be said about time management and how expeditiously a hands-on evolution can be performed if the students don’t have to think about their actions.

However… When the instructor makes the decisions, the students are not learning. [tweet this] If the student doesn’t have to perform a size-up and make their own decision, they are not learning how to make a decision and this can be very dangerous. To further complicate matters, during live fire evolutions, the decision to go or not go… is always “GO!” This is a problem too.

It doesn’t really matter if the decision is made by the officer on the crew or if it is made by the instructor. In training, if the decision is always “GO” then no one is learning how to make a decision. [tweet this] This is a problem.

What is a decision?

A decision is a choice among alternatives. If there are no alternatives, then there is no decision to be made. If a crew gets geared up to make an entry at a training burn and the officer of the crew doesn’t consider no-go as an option, then no decision was made. The pre-determined action was “GO” with no thought required.

If the hose lines for the live burns are laid out on the ground already and all the hose lines are the same size and the officer doesn’t have to give consideration to the hose line size needed based on the size of the fire or the size of the building, then no decision was made. The pre-determined action was to take the only hose line on the ground and, of course, take it inside.

Chief Gasaway’s Advice

We can do better. We should do better. We owe it to our company officers to teach the process for decision making (and there is a process for making high-risk, high-consequence decisions under changing conditions). This “process” discussed thoroughly during the Mental Management of Emergencies class (which coincidentally has become one of my most popular programs). This is good thing because that program teaches company officers and incident commanders how to use situational awareness as the foundation for making high-risk, high-consequence decisions.

We can do better. We should do better. We owe it to our company officers to teach the process for decision making (and there is a process for making high-risk, high-consequence decisions under changing conditions). This “process” discussed thoroughly during the Mental Management of Emergencies class (which coincidentally has become one of my most popular programs). This is good thing because that program teaches company officers and incident commanders how to use situational awareness as the foundation for making high-risk, high-consequence decisions.

Decision making is not something that is being taught to many firefighters and officers. I once had an instructor attending one of my programs make the point that new firefighters should not be taught how to make decisions. That’s the job of the officer. My response was: Every member should be taught how to form situational awareness and how to make a decision. [tweet this]

I asked this instructor if the entry-level firefighters are not taught the process for decision making, then when in their training does that happen? He quickly replied it is part of their officer development training. I could not help myself. For in this room, at that time, there were no less than fifty company officers present. So I polled the room. “Raise your hand if, once you were promoted to company officer you were provided training on the process of how to make high-risk, high-consequence decisions using situational awareness as the foundation.” Two or three hands went up. That means 45+ hands didn’t go up which was much more telling. What we SHOULD be doing… and what we are ACTUALLY doing… are miles apart.

We can teach the processes for situational awareness development and high-risk decision making in a classroom. So you don’t have to eat up valuable drill-ground time teaching this. In fact, once you get on to the drill ground, the focus should simply be to practice the formation of situational awareness and to practice making high-risk, high-consequence decisions based on fireground factors.

And here’s a hint for the instructors: If the scenarios are developed properly, some are going to be no-go and exterior operations. And when the company officer makes the decision to no-go, the actions of the crew support the decision (e.g., spray the water on the burn building from the outside).

Action items

1. Discuss if and how decision making processes are being taught to your firefighters, company officers and commanders. Identify areas of opportunity to improve how these processes are taught and practiced.

1. Discuss if and how decision making processes are being taught to your firefighters, company officers and commanders. Identify areas of opportunity to improve how these processes are taught and practiced.

2. Discuss how decisions are made during training in your department. Identify opportunities to shift the decision making from the instructors to the students.

3. Discuss how situational awareness serves as the foundation for good decision making. Identify ways to use simulation software on the training ground so participants see smoke and fire conditions (and various building construction types) that they are never going to see if the only thing they are looking at is a steel or concrete building with a propane or wood pallet fire burning inside.

_____________________________________________________________

The mission of Situational Awareness Matters is simple: Help first responders see the bad things coming… in time to change the outcome.

Safety begins with SA!

_____________________________________________________________

Share your comments on this article in the “Leave a Reply” box below. If you want to send me incident pictures, videos or have an idea you’d like me to research and write about, contact me. I really enjoy getting feedback and supportive messages from fellow first responders. It gives me the energy to work harder for you.

Thanks,

Email: Support@RichGasaway.com

Phone: 612-548-4424

Facebook Fan Page: www.facebook.com/SAMatters

Twitter: @SAMatters

LinkedIn: Rich Gasaway

YouTube: SAMattersTV

iTunes: SAMatters Radio

Great read thanks for all the effort. Congratulations on the public speaking certificate, I know three fireman who would rather run in that yellow house with fire blowing out of every opening than vet up and teach!

Chris Stanley

Chris,

Thanks for the feedback. I really appreciate our support if my mission and for contributing.

Rich

Many years ago I often taught young officers and FF’s that at time of any decision you make, only you are standing in your boots and the outcome will be the final judge of your decision. Great program chief!

All great facts you bring much needed light to. I once asked why recruits were not taking a TIC into the burn building during a training evolution (as we would expect them to on a real fire). We often forget the forest for the trees. Keep it up Chief!