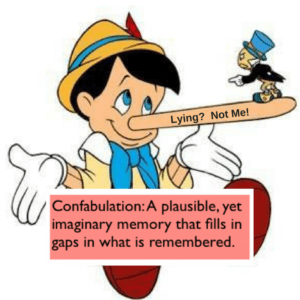

Confabulation may sound better than lying, but it’s no less dangerous. One of the most amazing demonstrations I do during my situational awareness programs is to show how a person, when placed under stress, will lie. Only in the world of neuroscience, we don’t call it lying, we call it confabulation.

You won’t do it on purpose but you may do it, nonetheless, and if you do, it can have a significant impact on your situational awareness and the situational awareness of those to whom you are telling your untrue stories. So let’s explore the brain phenomenon of confabulation

During my demonstration I am explicit in my instructions to the participant: “Don’t say anything that is not true.” Then I conduct the experiment and the attendees get to observe the participant, unknowingly, lie to me. The odd thing is, when the experiment is complete I poll the audience, asking them if the participant lied. Their resounding answer is almost always: “No!” When in fact, the participant made multiple untrue statements.

What is a lie

We often think of a lie as saying something that is untrue to avoid the consequences that come from telling the truth. People most often lie to avoid getting into trouble or to harm someone else. In my real time experiment, the participant won’t get into trouble if they tell an untruth so the attendees don’t see it as lying. By the socially accepted definition, the participant did not lie. But he or she does not tell the truth.

Confabulation

In neuroscience circles we had to find a way around this propensity to deny that untruths were told. Scientists coined the word “confabulation” to explain how a person’s brain makes up information, albeit false information, to help them make sense of situations that otherwise would appear to be insensible.

How we confabulate

When confronted with information that does not make sense, or when faced with large volumes of information, or when the information is complex and detailed, your brain can start shedding details. Some of this shedding occurs because the information may be insensible. Some shedding may occur simply because there’s too much information to be processed and your brain becomes overwhelmed.

When confronted with information that does not make sense, or when faced with large volumes of information, or when the information is complex and detailed, your brain can start shedding details. Some of this shedding occurs because the information may be insensible. Some shedding may occur simply because there’s too much information to be processed and your brain becomes overwhelmed.

The holes left in the story can then be filled-in with what your brain thinks makes sense, even if it’s not true. You can do this so quickly that it is sometimes called spontaneous confabulation. That’s right, your brian can make up stories that are absolutely untrue, in a split second, and you’ll never know the difference. Scary, huh?

This is not just speculation. Researchers can actually use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to show which brain regions are activated when you are confabulating a story. In other words, even when you don’t know you’re lying, the fMRI tells the truth.

The Situational Awareness Tie-In

Imagine a forward positioned team leader reporting to command the details of a situation. If the team leader encounters something that is unusual or does not make sense in his or her brain, or if the team leader is trying to convey details of a dynamic, detailed, and complex environment, his or her brain can play its trickery and distort the facts with what it imagines to be the truth, even if it’s not.

I know, it’s hard to believe, but you’ll have to trust me, it can happen. Anyone who’s attended my Fifty Ways to Kill a First Responder program has seen this phenomenon play out right in front of everyone in attendance. It’s hardly believable until you see it with your own eyes.

This means the updates and progress reports offered by team leaders may only be a partial representation of the truth. They’re not withholding information or changing facts on purpose. In nearly all cases they’re not even aware they’ve done it. But, as you can imagine, in an emergency scene the consequences can be significant.

If the commander receives an update or progress report that is not accurate, it is going to impact the commander’s situational awareness. This, in turn, can lead to flawed decision making. The causation of the flawed decision may not be realized until the after-action report when communications are matched to the actual conditions. It’s important to remember that this is NOT being done on purpose.

Rich Gasaway’s Advice

When receiving an update or progress report, always listen with a skeptical ear. This means you are aware of the confabulation phenomenon and thus, you seek to match what you’re being told with what you are seeing. If it does not match up, you may be confronting a confabulation. When 2+2 does not equal 4, start asking questions. Pump the team leader for more information about what is going on.

When receiving an update or progress report, always listen with a skeptical ear. This means you are aware of the confabulation phenomenon and thus, you seek to match what you’re being told with what you are seeing. If it does not match up, you may be confronting a confabulation. When 2+2 does not equal 4, start asking questions. Pump the team leader for more information about what is going on.

Tell the team leader that what you are observing does not match what they are saying. Don’t be confrontational. Remember, the team leader won’t know they’re confabulating. Confrontation may only cause them to defend their position stronger. In their mind, their story (even it it’s confabulated) makes sense to them.

Action Plan

1. Discuss a time when you found yourself confabulating at an incident scene (if you even know that you did at the time). Alternately, discuss a time when you knew someone else confabulated.

1. Discuss a time when you found yourself confabulating at an incident scene (if you even know that you did at the time). Alternately, discuss a time when you knew someone else confabulated.

2. Discuss some steps that can be taken to confirm accurate information if you suspect the information you are receiving is confabulated.

3. Discuss strategies for how to address a person who is confabulating a story (keeping in mind they don’t know they’re doing it). Avoiding confrontation is important!

About the Author

Richard B. Gasaway, PhD, CSP is widely considered a trusted authority on human factors, situational awareness and the high-risk decision making processes used in high-stress, high consequence work environments. He served 33 years on the front lines as a firefighter, EMT-Paramedic, company officer, training officer, fire chief and emergency incident commander. His doctoral research included the study of cognitive neuroscience to understand how human factors flaw situational awareness and impact high-risk decision making.

_____________________________________________________

If you are interested in taking your understanding of situational awareness and high-risk decision making to a higher level, check out the Situational Awareness Matters Online Academy.

CLICK HERE for details, enrollment options and pricing.

__________________________________

Share your comments on this article in the “Leave a Reply” box below. If you want to send me incident pictures, videos or have an idea you’d like me to research and write about, contact me. I really enjoy getting feedback and supportive messages from fellow first responders. It gives me the energy to work harder for you.

Let’s Get connected

Facebook: SAMatters

LinkedIn: Rich Gasaway

LinkedIn: Situational Awareness Matters

Twitter: Rich Gasaway

Youtube: SAMattersTV

itunes: SAMatters Radio

Stitcher Radio: SAMatters Radio

Google Play: SAMatters Radio

iHeart Radio: SAMatters Radio

Excellent article Doc. Reiterates confirmation from various sources as well.

Thanks Chief for your feedback and your continued support. I hope we get the opportunity to visit again soon. Rich

Rich,

I had this happen to me during a simulation training exercise. During the after-action review, I was asked why I made a particular decision based upon the scene reports that were provided to me. After lengthy debate (denial) that I made such a decision, the training lead replayed the training exercise which was video taped. To my surprise, there I was giving orders that, only seconds before, I was adamant about not giving. To say I was guilty of confabulation would be an understatement.

Thanking you sharing your wisdom,

Steve

Steve,

I have done the same thing… and interviewed MANY who have. The challenge is we never know we are doing it while it’s happening. Thanks for sharing your experience with the readers.

Rich

Great artical Rich.