One of the most frequent questions I get asked during the Mental Management of Emergencies and Fifty Ways to Kill a First Responder programs is: How can a novice responder develop expert knowledge when the number of fires are going down? It’s a great question and a great concern because so much of situational awareness and making good decisions in high stress, high consequence environments hinges on having stored expert knowledge.

One of the most frequent questions I get asked during the Mental Management of Emergencies and Fifty Ways to Kill a First Responder programs is: How can a novice responder develop expert knowledge when the number of fires are going down? It’s a great question and a great concern because so much of situational awareness and making good decisions in high stress, high consequence environments hinges on having stored expert knowledge.

Is there any hope for the novice responder? Can he or she develop and maintain situational awareness and make good decisions with limited real-life experience? The answer is: There may be a solution and it is one rooted in brain science. Let’s explore how the brain learns and recalls information that aids in the decision making process.

Defining “Expert”

Many responders consider themselves experts. Some have worked very hard to achieve expert knowledge and the moniker is well deserved. Others, unfortunately, think they are experts when, in fact, they may be far from it.

Many responders consider themselves experts. Some have worked very hard to achieve expert knowledge and the moniker is well deserved. Others, unfortunately, think they are experts when, in fact, they may be far from it.

This is critical because there is a fundamental difference between how novices and experts make decisions – especially under stress.

Competency

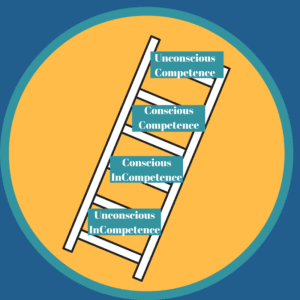

One way to look at expertise is to look at competency – how much knowledge does the individual possess and how competent are they in applying their knowledge. Those who have studied expertise put the development of competency in a four-step continuum.

Stage 1: Unconscious Incompetence

This is where we all begin our journey to expert knowledge, without regard to the field of study. We all start with no knowledge and we don’t know what we don’t know. This is why it is termed Unconscious (unaware) Incompetence (lacking knowledge, skills and abilities). This person might be described as being blissfully ignorant. They don’t even know what they don’t know. A first responder who is at this level of competency might respond to a call where some critical clue or cue was present and say: “I didn’t even see/hear it.”

Stage 2: Conscious Incompetence

Once a person begins to acquire knowledge through training and educational opportunities they begin to gain an understanding about how complex their chosen field of study can be. They are actively learning but may still lack experience. This person begins to realize there is a lot they don’t know about their chosen field of study. Thus, the term Conscious (aware) Incompetence (lacking knowledge, skills and abilities). This person might be described as afraid because they have learned enough to understand there’s a lot they need to learn, but have not yet. They now know there’s a lot they don’t know. A first responder who is at this level of competency might respond to a call where some critical clue or cue was present and say: “I saw/heard it, but I didn’t know what it meant.”

Stage 3: Conscious Competence

As a person continues to acquire knowledge, skills and abilities (i.e., experience) they begin to gain confidence because they now know enough to make a good decisions – though it may require a good deal of conscious analysis and brain power because they have to think about their lessons and apply them thoughtfully to the situation. This person is aware (conscious) their knowledge is being applied in a meaningful way and it is aiding in their good decision making (competence). For the most part the decisions are good, even if they take longer to come up with. A first responder who is at this level of competency might respond to a call where some critical clue or cue was present and say: “I saw/heard it and I knew what I needed to do.”

Stage 4: Unconscious Competence

This is the pinnacle of competency development and one that everyone who makes high risk, high consequence decisions should strive to achieve. This person possesses so much knowledge and experience that decisions are made intuitively – subconsciously if you will. The expert knowledge possessed in the subconscious level of their brain is tapped (by forming pattern matches to previous training and experiences) and the decision maker knows, intuitively, what to do. Their knowledge resides at the subconscious level (unconscious) and they have a high degree of expert knowledge (competence). A first responder who is at this level of competency might respond to a call where some critical clue or cue was present and say: “I just knew what to do.”

A Recipe to Develop Expertise

Some responders reading this article are not going to like what I’m about to say. However, know that what I am about to say is not guesswork. It is science. Researchers have spent a great deal of time trying to figure out how much effort it takes for someone to develop expert knowledge. They have studied many disciplines including doctors, musicians and professional athletes. The results have been reasonably consistent.

To acquire the knowledge, skills and abilities to make expert-level decisions requires ten years of experience. Those readers with ten+ years are now in celebration mode. You’ve reached the summit. But don’t break out the champagne just yet. Expertise is developed with 10 years of experience IF the expert developed their knowledge through learning and practicing their skill for two hours a day, five days as week for ten years. That’s more than 5,000 hours of learning and practicing over a ten year period. Most first responders possess nowhere near that level of expertise. Many, however, think they are experts and that can be dangerous.

Accelerating the Learning

Is there anything you can do to accelerate the process, given the downward trend in the number of actual fires? The answers is: Yes! There is something you can do to accelerate your learning and many people have acquired expert knowledge using this valuable shortcut.

To understand how you can shortcut the process, let me explain one fundamental concept of learning that many people are not aware of. Your brain cannot distinguish fact from vividly imagined fiction. It’s true. If you vividly imagine something as being real, your brain stores the experience as if it were real and that becomes knowledge that can aid in decision making.

To understand how you can shortcut the process, let me explain one fundamental concept of learning that many people are not aware of. Your brain cannot distinguish fact from vividly imagined fiction. It’s true. If you vividly imagine something as being real, your brain stores the experience as if it were real and that becomes knowledge that can aid in decision making.

Tricking your brain can be challenging however. Your brain is smart and it has a pretty good bullshit detector built in. So to get your lessons to store deep into long term memory (which is where you want them to be to aid in your unconscious competency) you need to make the lessons… emotional.

Yes, emotions cause lessons to seat deeper into memory and helps your brain to recall them too. This means when you train it needs to be: Realistic, repetitive and emotional. When you read case studies of near miss or casualty events – read them as though you’re actually there and the responder who is dying is someone you know. Make it real. Make it emotional. Feel it… hear it… smell it… employ as much sensory stimulation as you possibly can. The more emotion it is when you read it, the more “real” it is when your brain stores it.

By doing this, two hours a day for ten years, you can then develop expert knowledge and perform (make decisions) at the unconscious competent level.

Rich Gasaway’s Advice

I have said it many times… here in Situational Awareness Matters… and broadcasted across my social media channels. I have proclaimed it during programs to audiences worldwide: You cannot train too much for a job that can kill you!

I have said it many times… here in Situational Awareness Matters… and broadcasted across my social media channels. I have proclaimed it during programs to audiences worldwide: You cannot train too much for a job that can kill you!

Some aspect of how to do our jobs better and safer should be on or minds (almost) every day. Reading, training, watching videos, discussing best practices with others, conducting mental simulations, using simulation software, table-top exercises, pre-planning… the list goes on and on.

Strive to end each day being a little bit smarter than when you started the day. If you do that on a regular basis, you will accelerate the development of expertise and this will improve both situational awareness and decision making.

Action items

1. Discuss your progression through the competency development stages. Conduct an honest assessment of where you are on the progression as it relates to various aspects of your position. (Hint: You may be at Stage 4 in some areas, but at Stage 1 or 2 in others).

1. Discuss your progression through the competency development stages. Conduct an honest assessment of where you are on the progression as it relates to various aspects of your position. (Hint: You may be at Stage 4 in some areas, but at Stage 1 or 2 in others).

2. Discuss where other members of your crew are on the competency development stages. Devise a plan for how to help them build greater competency using methods to accelerate learning.

3. Discuss ways you could develop competency every day. Give some tangible examples. Remember if you are doing simulations, start basic and build complexity into them over time. Challenge yourself by brainstorming alternative solutions to problems. Go beyond plucking the low hanging fruit (the easy solution).

_____________________________________________________

If you are interested in taking your understanding of situational awareness and high-risk decision making to a higher level, check out the Situational Awareness Matters Online Academy.

CLICK HERE for details, enrollment options and pricing.

__________________________________

Share your comments on this article in the “Leave a Reply” box below. If you want to send me incident pictures, videos or have an idea you’d like me to research and write about, contact me. I really enjoy getting feedback and supportive messages from fellow first responders. It gives me the energy to work harder for you.

Thanks,

Email: Support@RichGasaway.com

Phone: 612-548-4424

SAMatters Online Academy

Facebook Fan Page: www.facebook.com/SAMatters

Twitter: @SAMatters

LinkedIn: Rich Gasaway

YouTube: SAMattersTV

iTunes: SAMatters Radio

Excellent as always. Thanks Rich, for all you do.

Brian,

Thank you for the feedback and your support. I appreciate it very much!

Rich

Thank you for the wonderful techniques that you share sir, what else can we do to enhance decision making skills?

A great read even when waiting for take off from Las Vegas Nevada to Calgary Chief!