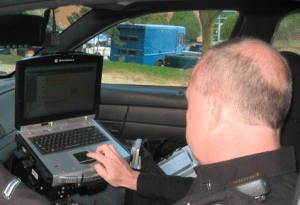

I am seeing an increase in the use of mobile data computers as a tool used by incident commanders. Commanders are using computers to capture and manage information, aid in decision making and in some cases as a tool in the development of situational awareness . On the surface, it would appear that situational awareness could improve if command vehicles were equipped with technology that would aide in data and information management. However, there may be danger lurking in the shadows. Let me explain…

Mobile data computers can be a very valuable data and information management tool. Depending on the complexity of the software, commanders can track responding and arriving companies, look up building information, even track personnel accountability, all of which can help build and maintain situational awareness. But technology can also hinder the ability of the commander to develop and maintain situational awareness.

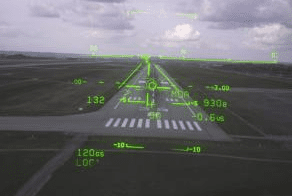

The flight deck of a modern airplane contains a plethora of screens and gauges designed to help improve a pilot’s situational awareness. One phenomenon that can occur in a work environment replete with technology is the potential to fixate attention on the displays and consequently miss something else that was happening in the environment.

Commercial airline pilots are assisted by computers in nearly every aspect of flying a plane. Yet it is possible for a pilot to fly a perfectly good aircraft into the ground. How could this happen? A pilot can become fixated on their displays and the volume of data they must comprehend and in the process forget about the need to capture other clues and cues in their environment including looking out the windshield. As incomprehensible as that sounds, it has been a contributing factor to both aviation near miss and casualty events.

Technology to help keep your head up

One of the solutions applied in aviation to help alleviate the head’s down situation was to created a head’s up display that would project critical flight information on to the windshield. This way pilots would not have to look down to see critical information. They could see it while, simultaneously, looking out the windshield. Problem solved, right? No quite.

Hocus focus

The eye can only focus on one thing at a time. If the pilot’s eye is focused on the data being projected on the head’s up display, everything beyond the windshield will be a blur. Likewise, if the pilot is focusing beyond the windshield, then everything on the head’s up display will be a blur.  In my Mental Management of Emergencies class I spend time discussing how the eyes work and how the brain processes information.

In my Mental Management of Emergencies class I spend time discussing how the eyes work and how the brain processes information.

Visual processing of information is an important component in the development of situational awareness. The eyes can only focus on one finite piece of geography at a time. Anything outside the focal point will be a blur. I use several powerful exercises to demonstrate this in the classroom. The students most surprised are those who think they are good at visual multitasking. When the exercises are done, they don’t think that any more.

Simply know the eye can only focus on one finite thing at a time. Let’s test it. Focus on the dot in the middle of the screen and, at the same time, read the line below the dot.

If you’re honest with yourself, you could not read this line without shifting your eyes to read each word.

Heads’s up displays

Ok… back to the problem of the head’s up displays used by pilots. The logic was if information was projected on to the windshield, the pilot would be able to see things beyond the windshield. The technology was tested, thankfully, in a flight simulator. Pilots used head’s up displays to read data essential to landing the aircraft. In every case, the pilots landed flawlessly. Success!

Ok… back to the problem of the head’s up displays used by pilots. The logic was if information was projected on to the windshield, the pilot would be able to see things beyond the windshield. The technology was tested, thankfully, in a flight simulator. Pilots used head’s up displays to read data essential to landing the aircraft. In every case, the pilots landed flawlessly. Success!

Hold on just a moment, Captain Over, before popping the corks on the bubbly, you should know that a significant number of the pilots also missed seeing an airliner that was on its runway while on approach. In aviation parlance this is called a runway incursion. In lay terms, you might say there’s about to be one big-ass crash.

Task fixation

A potential pitfall of technology is it can be easy to become fixated on the data terminal. This can occur for several reasons. If the viewer is less than completely familiar with the software, he or she may become fixated on trying to understand how to navigate between screens and/or how to read or interpret the data on the screens.

Learning curve

As with any new technology, there is a learning curve for the development of proficiency. A commander who is unfamiliar with the technology, both software and hardware, will take longer to accomplish the task (meaning more time spent head’s down).

As with any new technology, there is a learning curve for the development of proficiency. A commander who is unfamiliar with the technology, both software and hardware, will take longer to accomplish the task (meaning more time spent head’s down).

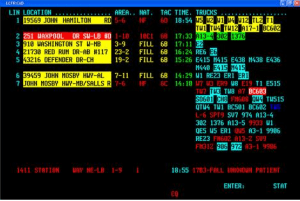

The commander may also become overwhelmed with the shear volume of data available on the screen(s). Not knowing which data is essential and which data is nice to know, which data is critical and which data is unimportant, may cause the commander to read all of the data, which can lead not only to information overload but can also attribute to a long period of time where the commander’s attention is fixated on the screen. If the data is changing, as might be the case with software designed to track air usage and/or personnel movement, the commander may become fixated on the screen for fear of missing some piece of new information that changed while he or she wasn’t looking.

If the data is changing, as might be the case with software designed to track air usage and/or personnel movement, the commander may become fixated on the screen for fear of missing some piece of new information that changed while he or she wasn’t looking.

Take for example a terminal that displays air usage and biometric data on the wellness of personnel operating in an IDLH environment. Depending on how many personnel are being tracked and the volume of information being displayed, this can easily become a point of visual fixation and information overload.

Trust the technology or trust your intuition?

Technology can also impact situational awareness when the data on the display does not match the intuition of the commander. Humans are wired to trust intuition and for good reason. Intuitive judgment comes from a collection of life’s experiences and relies on the brain’s powerful pattern matching abilities. In contrast to the hard facts being spit out by a computer terminal, it can be very challenging for a commander to explain the basis of his or her intuitive knowledge and judgment.

So what happens if/when the computer indicates a situation inconsistent with the commander’s intuition? Who’s right and who’s wrong? The answer to that question often does not play out until the incident is over. If the commander is new to using technology there can be an inherent distrust in computer-generated data. The commander may also believe his or her situational awareness and personal judgment is better than the computer’s. In some well-documented research, this has indeed been the case.

Human situational awareness and judgment can, in some cases, be better than any intelligence generated by a computer. When a conflict exists between the computer and the brain, a decision must be made by the human – trust the computer or trust the brain. In some cases a human will discount the computer as being flawed or malfunctioning and rely on their human judgment. While computer errors are not impossible the problem often is not a result of inaccurate data but rather the inaccurate interpretation of the data.

A commander may also discount his or her own intuition, placing complete reliance on the technology – blindly trusting the computer. This can be a big mistake because computer programs have their limitations. No computer is equipped with the sensing probes, software or processing capacity to capture, interpret, comprehend and synthesize data as effectively as the human brain.

Barriers to situational awareness

When I conducted my research as part of my doctoral dissertation, I identified 116 potential barriers to situational awareness. The top fifty of those barriers became the foundation of a powerful one-day program I conduct worldwide entitled Fifty Ways to Kill a First Responder. Fixation on technological displays was among the barriers I evaluated. However, technology barriers did not make my top fifty list (and therefore are not part of the Fifty Ways program). Why? Because at the time I conducted my research (2006-2009) mobile data computers were not widely used by incident commanders.

When I conducted my research as part of my doctoral dissertation, I identified 116 potential barriers to situational awareness. The top fifty of those barriers became the foundation of a powerful one-day program I conduct worldwide entitled Fifty Ways to Kill a First Responder. Fixation on technological displays was among the barriers I evaluated. However, technology barriers did not make my top fifty list (and therefore are not part of the Fifty Ways program). Why? Because at the time I conducted my research (2006-2009) mobile data computers were not widely used by incident commanders.

As the technology improves, and becomes more advanced, and sales people become better at pitching their software as the solution to improving commander situational awareness, I predict emergency services will see a marked impact in commander situational awareness from a fixation on software screens and computer-generated data.

Chief Gasaway’s Advice

When using technology for data and information management, be aware of the potential shortcomings both in the design and capabilities of the technology as well as the potential to have your situational awareness impacted from the technology.

When using technology for data and information management, be aware of the potential shortcomings both in the design and capabilities of the technology as well as the potential to have your situational awareness impacted from the technology.

Keep in mind that the data on the terminal is only a small fraction of the clues and cues essential to situational awareness good decision making. In many cases, the data on the computers may not even be among the most important information yet can attract and consume all of your attention.

Assign duties that require attention to computerized information to others. For example, software that tracks crew locations, air supply and biometrics may be best monitored by a command aide, helping the commander avoid using precious cognitive resources to process volumes of information on a micro-task.

Ensure users of the technology receive a thorough orientation on the use of the software and hardware and ensure they practice using it on a regular basis. Using the technology for both smaller and larger incidents is essential. Refraining from using automated technology until you have ‘the big one’ may be a recipe for failure.

The skills are better developed and honed during smaller, less stressful, perhaps less consequential, incidents. So long as you are not using homemade or first generation experimental software, trust the technology and the data it produces. Knowing how to interpret the meaning of the data is also essential.

Verify the computer data with back-up systems and processes. Capture additional information to validate the findings of the technology. You can also, conversely, use the technology to validate or refute your human intuition.

Discussion Questions

1. What advantages have you experienced from using mobile data computers to help manage incident data and information?

1. What advantages have you experienced from using mobile data computers to help manage incident data and information?

2. What disadvantages have you experienced from using mobile data computers to help manage incident data and information?

3. What advice would you offer to departments seeking to implement mobile data computers for incident management? ___________________________________________________________

The mission of Situational Awareness Matters is simple: Help first responders see the bad things coming… in time to change the outcome.

Safety begins with SA!

___________________________________________________________

Post your answers to the discussion questions or share your comments on this article in the “Leave a Reply” box below. If you want to send me incident pictures, videos or have an idea you’d like me to research and write about, contact me. I really enjoy getting feedback and supportive messages from fellow first responders. It gives me the energy to work harder for you.

Thanks,

Email: Support@RichGasaway.com

Phone: 612-548-4424

Facebook: www.facebook.com/RichGasaway

Facebook Fan Page: www.facebook.com/SAMatters

LinkedIn: Rich Gasaway

Twitter: @RichGasaway

Twitter: @SAMatters

YouTube: RichGasaway1

YouTube: SAMattersTV

iTunes: SAMatters

It’s truly very complex in this busy life to listen news on TV, so I only use the web for that purpose, and obtain the hottest information.