I recently received an inquiry from an SAMatters member asking my thoughts on front loading command personnel in the event of a Mayday. Specifically, the reader wanted to know if I thought it was a good idea. I could answer the question in one word: Yes. However, I like to help my readers build deep knowledge on matters related to first responder safety – ensuring they not only receive an answer but also an explanation that backs the answer. So let’s talk about staffing the command team.

I recently received an inquiry from an SAMatters member asking my thoughts on front loading command personnel in the event of a Mayday. Specifically, the reader wanted to know if I thought it was a good idea. I could answer the question in one word: Yes. However, I like to help my readers build deep knowledge on matters related to first responder safety – ensuring they not only receive an answer but also an explanation that backs the answer. So let’s talk about staffing the command team.

The command team

First, and foremost, I want to be explicit in sharing my thoughts on what it takes to command an incident with multiple companies working. I believe, and can support my assertions with science, that the cognitive demands of commanding a working incident with multiple companies performing multiple tasks requires the mental capacity of more than one person. Thus, incidents with multiple companies deployed should be commanded by a team, not an individual. Any individual who thinks they can keep track of the volume of information that needs to be processed and comprehended at a complex incident is either overestimating their abilities or in denial.

First, and foremost, I want to be explicit in sharing my thoughts on what it takes to command an incident with multiple companies working. I believe, and can support my assertions with science, that the cognitive demands of commanding a working incident with multiple companies performing multiple tasks requires the mental capacity of more than one person. Thus, incidents with multiple companies deployed should be commanded by a team, not an individual. Any individual who thinks they can keep track of the volume of information that needs to be processed and comprehended at a complex incident is either overestimating their abilities or in denial.

Cognitive capacity

The amount of information the average person can capture, process, comprehend and recall is limited. We all know that. But just how limited may be a little surprising. In 1956 Gregory Miller, a Princeton psychologist, set out to answer the question about how many pieces of unrelated information a person can capture, process, comprehend and recall. So how many pieces is it? Here’s a few hints: How many dwarfs did Snow White have? How many Natural Wonders of the world are there? Steven Covey wrote a book about the habits of highly effective people. How many habits did Steven write about?

The amount of information the average person can capture, process, comprehend and recall is limited. We all know that. But just how limited may be a little surprising. In 1956 Gregory Miller, a Princeton psychologist, set out to answer the question about how many pieces of unrelated information a person can capture, process, comprehend and recall. So how many pieces is it? Here’s a few hints: How many dwarfs did Snow White have? How many Natural Wonders of the world are there? Steven Covey wrote a book about the habits of highly effective people. How many habits did Steven write about?

By now you know the answer is seven. That’s exactly what Miller found out and his findings were published in a famous article titled The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information. It was Miller’s research that resulted in the creation of the seven-digit phone number system. His findings have been robustly confirmed in research conducted throughout the world. Suffice it to say, the working memory’s capacity to process information is quite limited.

When you add stress into the mix, the ability of the working memory to hold on to information can be adversely impacted. So much so, the seven pieces of unrelated information may drop to four or five. This means information may be lost (i.e., erased) and, once lost, may never be recovered. Now, let’s bring this limitation on to the emergency scene where a commander must manage an incident and a mayday.

Sorting it out

A working incident produces many pieces of information, some of it is important (i.e., critical to know) and much of it is not important (i.e., nice to know). Unfortunately, it takes mental processing capacity to determine what is important and what is not. In other words, if a piece of radio traffic is transmitted, the commander is not able to determine if the radio traffic is important or not until it is listened to, processed and comprehended. Then, and only then, can the determination of importance be made.

A working incident produces many pieces of information, some of it is important (i.e., critical to know) and much of it is not important (i.e., nice to know). Unfortunately, it takes mental processing capacity to determine what is important and what is not. In other words, if a piece of radio traffic is transmitted, the commander is not able to determine if the radio traffic is important or not until it is listened to, processed and comprehended. Then, and only then, can the determination of importance be made.

Unfortunately, this cannot be done without using precious working memory resources. If a commander is busy listening to one piece of verbal information determined to be important (perhaps, albeit prematurely), the commander may miss a competing piece of verbal information because the auditory control center in the brain is busy processing the first piece of information. The same things applies to cues and clues coming into all of the senses.

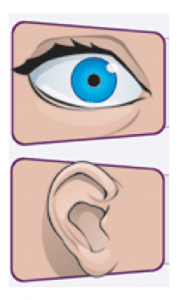

Audible is more vulnerable than visual

The potential to miss important audible clues and cues is more pervasive than missing important visual cues. This is because you cannot scan with your ears very effectively. You can only listen to audible information one word at a time. But you can visually scan a large volume of information (or a landscape) quickly and separate the important from non-important.

The potential to miss important audible clues and cues is more pervasive than missing important visual cues. This is because you cannot scan with your ears very effectively. You can only listen to audible information one word at a time. But you can visually scan a large volume of information (or a landscape) quickly and separate the important from non-important.

Audible processing can impact visual processing

Audible processing requires a lot of mental energy. This is because your ears take in an audible message that is then converted into a visual image. This requires the use of both auditor and visual processors. When there is a lot of audible information coming in to be processed, the visual processor can be adversely impacted. Your eyes will still be working fine, but the ability to comprehend the visual images may be altered or slowed of the visual processor is overloaded processing the images from audible information. In other words, you may be looking right at something but be unable to comprehend its importance.

Commanding the mayday

Now, let’s take what we just talked about and apply it to a working incident where there is a high volume of audible radio traffic (and perhaps face-to-face communications) to be processed and a high volume of visual information to be processed. The radio traffic is non-stop. The visual information constantly changing. Both require a high degree of vigilance and an enormous working memory capacity. If there is only one person in the command position trying to capture, process, comprehend and recall all of this information they are in a deficit position.

Now, let’s take what we just talked about and apply it to a working incident where there is a high volume of audible radio traffic (and perhaps face-to-face communications) to be processed and a high volume of visual information to be processed. The radio traffic is non-stop. The visual information constantly changing. Both require a high degree of vigilance and an enormous working memory capacity. If there is only one person in the command position trying to capture, process, comprehend and recall all of this information they are in a deficit position.

Add the complication of a mayday and the deployment of a rapid intervention team and the incident becomes exponentially more complex. The volume of audible and visual information is going to increase tremendously. The amount of stress the commander will be feeling will also increase significantly. This may, in turn, trigger a whole host of potential cognitive capacity issues for the commander. This is not the position a commander wants to find him or herself in.

Preloading command support

If you were asked to define the duties that need to be performed at a working residential dwelling fire, the list might include things like: Attack, back-up, exposures, search, vent, utilities, RIT, rehab, and water supply (and maybe a few more). Each of these tasks are best performed with a predetermined minimum number of responders.

If you were asked to define the duties that need to be performed at a working residential dwelling fire, the list might include things like: Attack, back-up, exposures, search, vent, utilities, RIT, rehab, and water supply (and maybe a few more). Each of these tasks are best performed with a predetermined minimum number of responders.

For the sake of this example, let’s say the numbers are: Attack (3), back-up (3), exposures (2), search (4), vent (3), utilities (2), RIT (4), rehab (1), water supply (1). That’s 24 responders (purposely excluding command functions at this point). Give or take for your local circumstances, the number can be predetermined.

The same can be done for the functions of command. Setting aside for a moment the NIMS positions of finance, logistics and planning, the command roles to be performed at a working residential dwelling fire might include: Commander, Operations, C-sector, Safety and Accountability (and maybe a few more). Now let’s break down down just the specific duties of the commander.

The commander must set the strategy, communicate the tactical objectives to the operations officer (or alternatively to all the companies arriving if there is no operations officer), track personnel assignments and progress (separate from accountability), monitor changing smoke and fire conditions, pay attention to building construction and decomposition of the structure, listen to all the radio traffic, write down important benchmarks, coordinate personnel movement, ensure adequate resources are on-scene or responding, etc. There’s a lot to be done and the duties can easily overwhelm the capacity of one person.

Now add a mayday into the mix and the deployment of the rapid intervention team. The commander, if alone, must now manage the mayday and manage the rest of the incident. It is a recipe for disaster from the perspective of being able to effectively manage the volume of information to be processed and a rapidly increasing stress environment. Expecting one person to handle this workload is almost a certain set-up for failure. A successful outcome at this point will be the result of luck as much as anyone’s skill.

Chief Gasaway’s Advice

The original question that gave rise to this article was: Should the command team be front loaded in the event of a mayday. My short answer was: Yes. My longer answer is: Do not wait until you have a mayday to front load your command team. Acknowledge that command is a team event and front load the incident with adequate command support to help the commander manage their massive cognitive load.

The original question that gave rise to this article was: Should the command team be front loaded in the event of a mayday. My short answer was: Yes. My longer answer is: Do not wait until you have a mayday to front load your command team. Acknowledge that command is a team event and front load the incident with adequate command support to help the commander manage their massive cognitive load.

Someone to monitor the radio. Someone to keep track of personnel movement and progress. Someone to coordinate tactical activities. Someone to watch out for the safety of personnel. Someone to assess the speed of the incident and to keep an eye on the progress the building is making toward conceding to the goal of gravity (to make the building fall down). Someone to supervise the deployment of the RIT. Someone to monitor the radio traffic of the mayday.

Clearly, commanding emergency incidents is complex and cognitive demanding. In nearly every casualty report I have evaluated, the commander was overwhelmed and was unable to keep up with the pace of change and the volume of information to be processed and comprehended. Front loading an incident with command personnel is part of the solution.

Discussions

1. Discuss a recent incident where the commander became overwhelmed and increased the potential for an adverse outcome (whether the bad outcome occurred is secondary).

1. Discuss a recent incident where the commander became overwhelmed and increased the potential for an adverse outcome (whether the bad outcome occurred is secondary).

2. What does your department do to ensure an incident commander does not become overloaded or overwhelmed with his or her workload at an incident scene?

3. Describe how your organization prepares for the massive spike in information and the impact of stress on personnel in the event a mayday is called.

The mission of Situational Awareness Matters is simple: Help first responders see the bad things coming… in time to change the outcome.

Safety begins with SA!

_________________________________________________________________________________

Share your comments on this article in the “Leave a Reply” box below. If you want to send me incident pictures, videos or have an idea you’d like me to research and write about, contact me. I really enjoy getting feedback and supportive messages from fellow first responders. It gives me the energy to work harder for you.

Thanks,

Email: Support@RichGasaway.com

Phone: 612-548-4424

Facebook: www.facebook.com/RichGasaway

Facebook Fan Page: www.facebook.com/SAMatters

LinkedIn: Rich Gasaway

Twitter: @RichGasaway

Twitter: @SAMatters

YouTube: RichGasaway1

YouTube: SAMattersTV

iTunes: SAMatters

We have added Chief officers to our MABAS system for several reasons, one is as Chief Gasaway points out, is information overload. Trying to keep track of every piece of information is difficult at best during the incident. By having added the Chief Officers on additional alarms assignment we have the ability to reassign them given a catastrophic event whether it be a mayday or a wall collapse or something a simple as a firefighter getting hurt outside the building.

Having that extra leadership helps greatly with situational awareness especially in small departments because the other Chief Officers may have experience something that you haven’t and can provide great advice to you during the event.

James,

Thank you for sharing your feedback on the article. Your practice of front-loading command officers is, indeed, a best practice and one that all fire departments should adopt. Extra command help is not a sign of weakness of the commander. Rather, it is a sign of strength in the commander. You’re doing things right in Kent!

Rich

Thanks for the insightful observation and explanation to my question about front-loading command. This is a critical conversation that must continue.

Just as the mind drives an individual’s skill and ability to perform tactically, command steers the collective motion of the companies to execute strategically.

To be ready to complete the mission, command must grow at the speed of the incident. Instead of planning for a “what if” moment, command should build for the “when it happens” event. The only way to do that is to be ahead of the incident.

My responses to your discussion questions:

1) I worked an incident as IC where we attempted a fast-attack on a rapidly-growing fire in a balloon-frame house converted to 3 apartments. Crews were assigned to fire attack, primary, back-up, RIC, water supply, and medical. Another command staff was assigned to safety. The incident reached a point where I realized that the tactics were not containing the fire. We had a total of 5 firefighters (including two officers) on floor-2. We ended up backing out and knocking down the fire with a larger hose line from the exterior. But if a Mayday had occurred when crews were working to exit floor-2 (it took them a little over a minute), command (me) would have been really overwhelmed. Thinking about it today, I would have re-directed my safety to supervise the Mayday assigning him crews as quickly as possible. This was the incident that got me thinking more about HOW I can better be ready for a mayday, or any other rapidly-changing event.

2) Per SOG, our department does notify some additional command staff, if a “working fire” is announced. Most of our field command staff (district captains and chiefs) do monitor working fire channels and respond without being dispatched. We are developing a better process to “expand command before the demand.”

3) Recently, our district chiefs began dialogue on building a better command on scene using decision making exercises with videos and hands-on training evolutions with crews. More important, we are talking about it!

Again, thanks for the great insight on a critical command issue. I am passing your article on to our rapid intervention committee and my fellow district chiefs for distribution.

Regards,

Billy

Billy,

Thanks for being the person who prompted the article with your question. I really appreciated the opportunity to address it. Thanks also for publicly sharing your responses to the questions. I am hopeful more readers will do this as we all learn more as we understand what other departments are doing (or in some cases not doing) to improve safety and situational awareness. Your contributions are making a difference. Keep up the good work!

Rich

My department has been front loading resources for a mayday following a near miss we had in January 2000. We added an Engine and Truck Company to our first alarm response to provide for a dedicated RIC Engine as well as another Officer on scene. In 2005 we began to add a second Battalion Chief to first alarm assignments for the reasons that James and Rich have stated.

We are now looking at front loading resources on multiple alarms that may be needed to manage a major RIC activation with a prolonged period of operation.

The fire service learns slowly and at times tragically, but we keep learning. Situations Awareness Matters and a proactive approach beats a reactive one every time.

Thanks for the work you do.

Mike,

Thank you for sharing your department’s best practice. The front loading is essential for many reasons, not the least being the limited reaction time when something goes bad and the need to ensure the commander does not fall behind when the dynamically changing incident becomes overwhelming due to a mayday. Keep contributing. Your input is very valuable for our readers.

Rich