Why is it so hard to let go of a decision or an action once we have committed ourselves to it? As I think back on my life, it is easy for me to identify a number of times where my situational awareness eroded and it led to bad decisions.

Why is it so hard to let go of a decision or an action once we have committed ourselves to it? As I think back on my life, it is easy for me to identify a number of times where my situational awareness eroded and it led to bad decisions.

I can attribute a number of those bad outcomes to my stubborn mind locking on to a decision or a plan of action that I was hell-bent on accomplishing. This often caused me to overlook – or even ignore – information that strongly indicated I was heading in the direction of a bad outcome. But it didn’t slow me down any. Why is it so hard to disengage?

The process of disengagement

To disengage requires collaboration among two faculties: Cognitive and kinesthetic. Stated another way, the mind must decide to disengage (that’s the cognitive part) and then the muscles must agree to follow the mind’s command and change the course of physical action (that’s the kinesthetic part). That seems easy enough. The mind orders the change and the body heeds the command.

The previous narration might better describe how we wish the process happened more than how it actually happens. Before your brain can issue a command to cease any action or to abandon any decision there is a lot of wrangling that goes on up there in the dark recesses of that three-pound blob of clay. And simply because the brain issues the cease and desist order doesn’t mean the body is necessarily going to immediately abide.

The previous narration might better describe how we wish the process happened more than how it actually happens. Before your brain can issue a command to cease any action or to abandon any decision there is a lot of wrangling that goes on up there in the dark recesses of that three-pound blob of clay. And simply because the brain issues the cease and desist order doesn’t mean the body is necessarily going to immediately abide.

Admitting error

One of the most difficult things a human can do is admit fault. [tweet this]

That’s not to say that everyone struggles from this shortcoming. Minnesotans and Canadians seem to be particularly adept at admitting their faults and saying “I’m sorry” a lot. Actually, I think it’s just their kind-heartedness and I’m sure it’s not limited to just them.

In general, we are wired with an internal drive to do things right – the first time. [tweet this]

In general, we are wired with an internal drive to do things right – the first time. [tweet this]

Humans learned early that mistakes repeated could have significant consequences to survival so our ancestors stored large repositories of decisions that resulted in good outcomes and decisions that resulted in a relative becoming lunch for a hungry predator.

Once we have been on the job for a while (i.e., experienced) we also possess a large repertoire of successful outcomes. We learn quickly what works (and hopefully what doesn’t). Then, on the job, we do what works and avoid what doesn’t. Seems easy enough.

But sometimes what we think will work, won’t. And oftentimes there were clues and cues present indicating that what we are doing isn’t working. But for some reason, the clues and cues are ignored. For admission that our plan is not working would be an admission of error – and admission of failure.

Failure

No one likes to fail and the more competitive you are the more you will resist the notion that your plan is not working or that you’ve made a bad decision. We spend a lot of time and effort building up our reputations as competent, responsible decision-makers. We take great pride in being technically competent and skilled practitioners.

To admit our decision is flawed or our action plan isn’t working is, to some, an admission of failure. [tweet this]

The notion of failing at something and standing in judgment of our peers or supervisors can evoke great fear in people and fear is a barrier to situational awareness.

Fear and Awareness

When a person is fearful of their safety, their awareness can actually improve as their vigilance is heightened and they become hypersensitive to the signs of danger. But when a person is fearful of failure, ridicule or embarrassment the opposite can happen. It can take on the appearance that vigilance is lowered and a person seemingly cannot see the potential consequences of their decisions or actions.

When a person is fearful of their safety, their awareness can actually improve as their vigilance is heightened and they become hypersensitive to the signs of danger. But when a person is fearful of failure, ridicule or embarrassment the opposite can happen. It can take on the appearance that vigilance is lowered and a person seemingly cannot see the potential consequences of their decisions or actions.

But it’s not vigilance that is the problem. It is acceptance of the clues and cues that are being fed into the brain by the vigilant senses. In other words, the senses are gathering the information that forms awareness but the brain is ignoring the information because it’s giving its attention to something else.

What could the brain possibly be giving its attention to that would be more important than clues and cues indicating that a decision or action may be flawed? Fear. More specifically, the fear of failure, the fear of ridicule and the fear of embarrassment.

Automatic action

Let’s assume for a moment that you are able to overcome the cognitive challenges of disengagement and your brain alters a decision or decides a different physical course of action is warranted. This should trigger a command for the muscles to stop what they are currently doing and route the energy to move your muscles in a new direction to a new goal.

Sometimes, however, the muscles seem to take on a mind of their own and do whatever they darn well please independent of the orders being issued by the central command (the cognitive brain). Think of the times when your “better judgment” told you NOT to do something yet, for reasons that may be difficult to explain or justify, you did it anyhow. Then, if whatever you did had a poor outcome, you probably caught yourself saying… or at least thinking… “I knew better.”

Once the muscles start an action it can be difficult to stop. [tweet this]

Once the muscles start an action it can be difficult to stop. [tweet this]

This happened to me recently when I found myself in a potentially dangerous situation late one night at a highway rest stop.

When I got out of my car I noticed there was a man in a vehicle parked next to mine. He seemed agitated and it appeared he was talking to someone though there was no one else in his vehicle. I assumed he was talking on his hands-free cell phone, thought little of it, and I went into the building to take care of my business.

When I came out of the building I immediately noticed he was still in his vehicle. As I walked down the sidewalk toward my vehicle it appeared that he looked up, saw me coming and exited his vehicle and started walking toward me. His actions set off my survival warning system.

My cognitive command was “Stop, turn around, go back inside where there are other people.” But my muscles ignored the order and just kept walking toward him. The event ended without incident as he walked right past me and into the building.

When I got into my car I had to take pause and ask myself why I didn’t listen to my intuition? Why did I just keep walking? What caused me to ignore the strong order being issued by central command? Yes, I actually do have the conversations inside my head. I can’t say I’m proud of that, but it does inspire much of my writing.

Dr. Gasaway’s Advice

It can be very difficult to disengage a decision or action. It may mean we have to admit we’ve made a mistake. [tweet this]

It can be very difficult to disengage a decision or action. It may mean we have to admit we’ve made a mistake. [tweet this]

It may cause us to feel like a failure. It may evoke a strong fear response – not for survival but to avoid ridicule and embarrassment.

There are also other situational awareness barriers in play that can impact the ability to disengage including Ego, bravado, overconfidence, denial, over-analyzing, attitude and more. Disengagement is a complex neurological process that requires great energy and commitment.

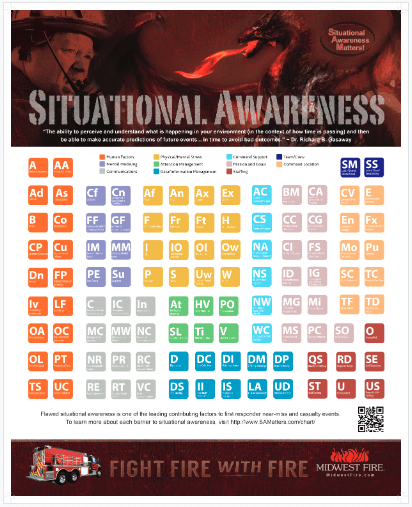

To learn more about the barriers that flaw disengagement and all aspects of situational awareness, CLICK HERE to visit a page on this website that contains the Periodic Chart of Situational Awareness Barriers. There, you will find all the barriers I have uncovered and researched listed conveniently on a chart like the one depicted below.

The more you know about the barriers that can erode situational awareness the better equipped you will be to manage or overcome them. [tweet this]

Action Items

1. Discuss the consequences of a time when you failed to disengage a decision or action.

1. Discuss the consequences of a time when you failed to disengage a decision or action.

2. Discuss the mental or physical challenges you have experienced when you attempt to disengage a decision or an action.

3. Discuss the consequences you’ve experienced from disengaging an action (e.g., ridicule, embarrassment, discipline).

4. Discuss strategies for disengaging both cognitive decisions and kinesthetic actions.

_____________________________________________________

If you are interested in taking your understanding of situational awareness and high-risk decision making to a higher level, check out the Situational Awareness Matters Online Academy.

CLICK HERE for details, enrollment options and pricing.

__________________________________

Share your comments on this article in the “Leave a Reply” box below. If you want to send me incident pictures, videos or have an idea you’d like me to research and write about, contact me. I really enjoy getting feedback and supportive messages from fellow first responders. It gives me the energy to work harder for you.

Thanks,

Email: Support@RichGasaway.com

Phone: 612-548-4424

SAMatters Online Academy

Facebook Fan Page: www.facebook.com/SAMatters

Twitter: @SAMatters

LinkedIn: Rich Gasaway

Instagram: sa_matters

YouTube: SAMattersTV

iTunes: SAMatters Radio

iHeart Radio: SAMatters Radio