In this article, we discuss three types of stress: Acute stress, episodic acute stress, and chronic stress. First responders can, and often do, experience all three. Stress can impact firefighter situational awareness and, equally concerning, stress can have devastating long-term impacts.

In this article, we discuss three types of stress: Acute stress, episodic acute stress, and chronic stress. First responders can, and often do, experience all three. Stress can impact firefighter situational awareness and, equally concerning, stress can have devastating long-term impacts.

As I was writing this article I recalled various times during my thirty years on the line where stress impacted my performance and my well-being. Responders are generally aware of the stresses that come from doing this job. Crawl into a burning building and you are going to feel stress. Deal with a major trauma (especially when it’s a child) and you’re going to experience stress. Ride in an apparatus in heavy traffic during an emergency response and you’re going to feel stress.

However, some responders don’t always realize when they’re feeling stress because stress doesn’t always feel like physical or emotional stress and strain. Endorphins and adrenaline stimulate the brain (in part to prepare you for the often discussed Fight or Flight Response). This stimulation may cause you to feel excited, not stressed. Firefighters exiting a structure after successfully extinguishing a fire may feel adulation, not stress. They may feel victorious. They may high-five. They may backslap. They’ve slain the dragon! They are excited. And, while it may not feel so, they are also stressed. Let’s spend some time examining three kinds of stress.

Acute stress

The most common form of stress a first responder is likely to experience on the job is acute stress. It manifests from recent events or with the expectation of upcoming events (i.e., stress from anticipation). Acute stress causes the release of chemicals that, in small doses can be very helpful – even life-saving. When the amount of acute stress is limited in duration, it may cause you to feel excitement or exhilaration. However, large doses of acute stress are not exhilarating. Rather, it can cause physical and mental fatigue.

The most common form of stress a first responder is likely to experience on the job is acute stress. It manifests from recent events or with the expectation of upcoming events (i.e., stress from anticipation). Acute stress causes the release of chemicals that, in small doses can be very helpful – even life-saving. When the amount of acute stress is limited in duration, it may cause you to feel excitement or exhilaration. However, large doses of acute stress are not exhilarating. Rather, it can cause physical and mental fatigue.

I experienced both ends of the acute stress spectrum while on a family vacation to Cedar Point Amusement Park. There, I got to ride an amazing roller coaster called Top Thrill Dragster. ‘Keep your arms down, head back, and hold on’ are the last words I remember hearing before I was launched down a track to 120 miles per hour. Then we were vaulted 420 feet into the air and back down again. Start to finish – 17 seconds of sheer terror. I was experiencing acute stress. But it sure didn’t feel like stress. I LOVED IT!

While waiting in the 1.5-hour long line to get on the ride I observed the faces and heard the screams of the stressed riders preceding me. This anticipation added to my level of acute stress.

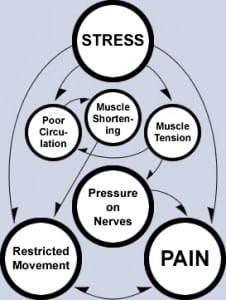

As the day went on and I rode more and more roller coasters I started to experience the physical and psychological symptoms of my prolonged acute stress. I got a tension headache, an upset stomach, my muscles were aching and much to the disdain of my kids, I had become irritable. I had been overexposed – you might say I overdosed – on acute stress chemicals.

As the day went on and I rode more and more roller coasters I started to experience the physical and psychological symptoms of my prolonged acute stress. I got a tension headache, an upset stomach, my muscles were aching and much to the disdain of my kids, I had become irritable. I had been overexposed – you might say I overdosed – on acute stress chemicals.

Because of its short-term nature, acute stress doesn’t have enough time to do the extensive damage associated with long-term stress. Symptoms of acute stress may include:

1. Anger

2. Irritability

3. Anxiety

4. Depression

5. Tension headache

6. Back pain

7. Jaw pain

8. Muscle tension

9. Stomach aches

10. Heartburn

11. Acid stomach

12. Flatulence

13. Diarrhea

14. Constipation

15. Irritable bowel syndrome

16. Elevation in blood pressure

17. Rapid heartbeat

18. Sweaty palms

19. Heart palpitations

20. Dizziness

21. Migraine headaches

22. Cold hands or feet

23. Shortness of breath

24. Chest pain

Because the list is so extensive and the symptoms can result from many other conditions, it is common for the symptoms of acute stress to be attributed to other causes.

Anyone can experience acute stress at any time. But first responders are, by the nature of their work and working conditions, more likely to experience acute stress. The good news is acute stress is highly treatable and manageable.

Episodic acute stress

Episodic acute stress occurs in people who suffer frequent bouts of acute stress. People in this category are often referred to as having lives filled with chaos and crisis. Always being in a rush. Always worrying about what can go wrong. Always being in an environment that is in disarray. Having high demands place in them (by others or their own expectations) can all attribute to episodic acute stress.

Episodic acute stress occurs in people who suffer frequent bouts of acute stress. People in this category are often referred to as having lives filled with chaos and crisis. Always being in a rush. Always worrying about what can go wrong. Always being in an environment that is in disarray. Having high demands place in them (by others or their own expectations) can all attribute to episodic acute stress.

While a first responder’s personal life may not be filled with chaos and crisis, he or she can be exposed to more than the average person’s quota of stress. Chaos and crisis, being rushed, worrying about things going wrong (for their own safety and the safety of those they are serving), working in rapidly changing environments and having high demands being placed on them (by elected officials, bosses, peers, and customers) are all part and parcel to the normal environment of a first responder. Even where a first responder has his or her personal life in order, the job itself can create episodic acute stress.

Imagine a person being in an environment that is excessively noisy, or bright, or cold, or windy. Repetitive and/or lengthy exposure to those elements is going to create stress. First responders who are repetitively exposed to lights and sirens, harsh environments and psychological trauma may suffer from episodic acute stress from repetitive and/or lengthy exposures.

The symptoms and consequences of episodic acute stress can include:• Being over-aroused

• Short-tempered

• Irritable

• Anxious

• Tense

• Nervous energy

• Feeling (and acting) rushed

• Abrupt

• Hostile

• Hypertension

• Chest pains

• Heart disease

Ironically, being exposed to someone exhibiting the symptoms of episodic acute stress can, in turn, increase the stress levels of those within their circle of influence. It can truly be a vicious circle.

Personalities

Episodic acute stress can be compounded by ‘Type A’ personality traits. Type A’s are often characterized as being highly competitive, impatient, and having an ever-present sense of urgency to everything. Type A’s can, at times, be aggressive and seemingly hostile – sometimes mildly, sometimes not.

Research into the cardiac impact of stress suggests Type A’s may be more likely to develop coronary artery disease as compared to the more docile, laid-back, relaxed ‘Type B’ personality counterparts. For better or worse, the action-oriented, fast-paced, high adrenaline rush inducing environment of public safety is a magnet for individuals with Type A personalities.

Episodic acute stress can be manifested from chronic worry also. First responders can be lulled into worrying about the unfavorable outcomes of everyday situations because they are exposed, repetitively, to people who are experiencing unfavorable outcomes in the throws of living everyday lives. For example:

A mother and her young son are walking down the sidewalk. An inattentive driver veers off course. The mother sees the car and instinctively jumps, avoiding being struck. But her seven-year-old son is struck by the car and suffers major head and thoracic injuries. He may not survive. This event is traumatic for the family, traumatic for the inattentive driver who caused the accident and traumatic for the first responders – police, fire and EMS who have to manage a crisis they did not create.

A mother and her young son are walking down the sidewalk. An inattentive driver veers off course. The mother sees the car and instinctively jumps, avoiding being struck. But her seven-year-old son is struck by the car and suffers major head and thoracic injuries. He may not survive. This event is traumatic for the family, traumatic for the inattentive driver who caused the accident and traumatic for the first responders – police, fire and EMS who have to manage a crisis they did not create.

The world we live in can be dangerous and bad things can happen with no forewarning. First responders see the consequence of this almost daily and it can not only have a cumulative effect, but it can also make the responder overly worrisome about the same consequences occurring in his or her own life or to his or her loved ones. This can contribute to stress-induced anxiety and depression.

Unlike acute stress which is short term and relatively easy to manage, episodic acute stress requires intervention that can include help from professional therapists. Treatment can last months or years.

Lifestyles

The first responder’s lifestyle – always being in the fast lane of life and the middle of the action – can be addicting. It can become ingrained and habitual. The responder may see nothing wrong with their ‘pedal to the metal’ lifestyle. They may never be able to see the impact stress is having on them. If they do see it, they’re likely to blame it on someone else or on external events.

The first responder’s lifestyle – always being in the fast lane of life and the middle of the action – can be addicting. It can become ingrained and habitual. The responder may see nothing wrong with their ‘pedal to the metal’ lifestyle. They may never be able to see the impact stress is having on them. If they do see it, they’re likely to blame it on someone else or on external events.

Pride and ego can also be a factor. A responder is used to being a caregiver, not a care-receiver and may be too proud to ask for help. He or she may also simply concede that the stress of their job is just part of who they are and what they do and resign themselves that nothing can be done about it.

Victims of episodic acute stress can be very resistant to admitting they have a problem and very resistant to changing anything in their lives to fix the problem. If their job-stress is compounded by (or maybe even exaggerated by) obesity, alcohol abuse, smoking, and/or a sedentary lifestyle, they may be very stubborn to change habits or seek help.

Chronic stress

Chronic stress is never thrilling and never exciting. It eats away at you every day, year after year and it can be tremendously destructive. Chronic stress occurs when a person is in a repetitively stressful environment and can’t see any way out of their situation. They feel trapped – so hopeless and so helpless they’ll actually give up on trying to find a solution.

Chronic stress is never thrilling and never exciting. It eats away at you every day, year after year and it can be tremendously destructive. Chronic stress occurs when a person is in a repetitively stressful environment and can’t see any way out of their situation. They feel trapped – so hopeless and so helpless they’ll actually give up on trying to find a solution.

The chronic exposure to stress over long periods of time can lead to desensitization. The stressed individual may become so accustomed to being stressed that they no longer feel stressed. They’re numb. They can, however, still feel the excitation and exhilaration of acute stress because acute stress is novel (new) while still ignoring the chronic stress.

Left undiagnosed and untreated, chronic stress and may lead to depression and suicide. The occurrence of a first responder suicide is very painful for responders. We’re all taught to be caregivers, to help others and when we lose one of our own we can feel tremendous guilt and remorse that we could not see it coming. Sometimes there are signs and symptoms, oftentimes there are not.

Sadly, a person can become so used to the feeling of chronic stress that he or she will actually feel uncomfortable when not in their stressful environment. I have seen this. Ok… I have experienced this. There have been many times when I was so stressed at work that I needed a vacation and took one. While on vacation I felt uneasy and, for reasons hard to explain, yearned to be back at work in the very pressure-cooker environment I took the vacation to get away from. I had become comfortable in my chronic stress environment.

_______________________________________________________________________

Dr. Gasaway’s Advice

There are several things we can do to help us manage the impact of stress on our bodies and minds. Here are a few:

There are several things we can do to help us manage the impact of stress on our bodies and minds. Here are a few:

- Exercise (30 minutes of moderate exercise, 3 times a week).

- Eating a balanced, low-fat diet.

- Drink plenty of water (8 glasses a day, minimum).

- Get plenty of rest (8 hours a day should be your goal, but there is a wide variation on the opinions of experts about how much rest is enough).

- Get a hobby (or an activity away from work that relieves stress and allows you to focus on something other than the stresses of the job.

- Be social. There is mounting evidence that social interaction can boost the immune system which helps lower stress.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Action Items

1. Discuss a time when you were acutely stressed and how it may have impacted your situational awareness or decision making.

1. Discuss a time when you were acutely stressed and how it may have impacted your situational awareness or decision making.

2. Discuss a time when you were chronically stressed and the effect it had on you.

3. Discuss strategies that can be used to manage stress on and off the job.

4. Discuss how co-workers may be able to help reduce the impact of the three types of stress discussed in this article.

_____________________________________________________

If you are interested in taking your understanding of situational awareness and high-risk decision making to a higher level, check out the Situational Awareness Matters Online Academy.

CLICK HERE for details, enrollment options and pricing.

__________________________________

Share your comments on this article in the “Leave a Reply” box below. If you want to send me incident pictures, videos or have an idea you’d like me to research and write about, contact me. I really enjoy getting feedback and supportive messages from fellow first responders. It gives me the energy to work harder for you.

Thanks,

Email: Support@RichGasaway.com

Phone: 612-548-4424

SAMatters Online Academy

Facebook Fan Page: www.facebook.com/SAMatters

Twitter: @SAMatters

LinkedIn: Rich Gasaway

Instagram: sa_matters

YouTube: SAMattersTV

iTunes: SAMatters Radio

iHeart Radio: SAMatters Radio

Doc!

Thank you for bringing this all to often ignored problem to light in yet another way! As you and I once discussed, because of some issues beyond my control, at birth I was left with the challenge in later years of finding ways to cope. I hope to be blessed to keep finding ways I have learned to help others! The one thing I want all who read this to know is no matter what stress level you are dealing with, you can survive! You are not trapped no matter how much your body tries to convince you otherwise! Fight the good fight and finish your race! One mans definition of success was ” just survive and then move on”. I have a passion for helping my brothers and sisters in emergency services that are dealing with these issues. Thank you for sharing and helping in such a language even I can understand! What a gift you have shared with us!

Sincerely,

Capn Chris Peak

IN