Welcome to Part 6 of the Understanding Stress series. In the last segment I shared with you some of the ill-effects stress can have on vision and I made brief reference to a term that may be new to many readers – auditory exclusion. This is an important consequence of stress that can have tremendous implications for situational awareness so I want to spend some additional time with it.

Welcome to Part 6 of the Understanding Stress series. In the last segment I shared with you some of the ill-effects stress can have on vision and I made brief reference to a term that may be new to many readers – auditory exclusion. This is an important consequence of stress that can have tremendous implications for situational awareness so I want to spend some additional time with it.

Auditory exclusion

Most firefighters and emergency responders are aware of tunneled vision because they were taught about it in their basic fire training program or perhaps in a medical training program. Tunneled hearing (a.k.a. auditory exclusion) is far less known, but every bit as dangerous.

There have been multiple research studies conducted on the impact of stress on hearing over the past 20 years. Most has been done with the military; Some with law enforcement; Very little with firefighters or EMS.

The physical and psychological responses to stress have been well-documented and summarized in the previous segments of this series so I won’t rehash them here. While training and techniques to control stress can prevent the severity of the response, make no mistake about it, once the hormonal dump occurs, you are no longer in control of the consequences.

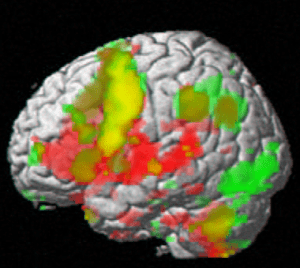

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans allow researchers to peer inside the brain, non-evasively, to see how the brain is functioning during the process of thinking and making decisions. Some pretty cool things have resulted from this technology. One lesson has been our understanding that the conscious brain is a horrible multitasker. (NOTE: The subconscious brain, on the other hand, is a wonderful multitasker.) Unfortunately, we see and hear with our conscious brains. This means the visual cortex and the audible cortex have to share resources or, in some cases, take turns processing information.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans allow researchers to peer inside the brain, non-evasively, to see how the brain is functioning during the process of thinking and making decisions. Some pretty cool things have resulted from this technology. One lesson has been our understanding that the conscious brain is a horrible multitasker. (NOTE: The subconscious brain, on the other hand, is a wonderful multitasker.) Unfortunately, we see and hear with our conscious brains. This means the visual cortex and the audible cortex have to share resources or, in some cases, take turns processing information.

In the presence of high-stress visual stimulation, the processing of audible information may be dulled. It may be turned off completely! Hence the word exclusion. If the audible cortex is still functioning but its acuity is turned down, the person may describe the sounds they hear as muffled or distant. During my research, one of my firefighter participants described this phenomenon as if they were hearing the teacher on a Peanuts cartoon.

The eardrums

During a high stress event the ears are working just fine… sort of. Physically, all the right parts are moving and taking in the sound waves but something can happen to diminish their processing. I recall reading one research study where participants were hooked up to an audiometer to test their base-level hearing. Then the participants were put on a treadmill and the hearing test continued as the heart rate increased (simulating the heart rate increase under stress). The results were very telling.

Once the heart rate got over 175, hearing diminished. The researchers concluded the blood rushing through the eardrums at that speed actually creates noise that cancels out what the person is hearing. That noise may come off as static, a hiss, or ringing in the ears. Hmmm… do firefighters and emergency responders working under stress ever experience heart rates above 175? You know they do. If your hearing is diminished due to a rapid heart rate, there is nothing you can do to rectify the situation other than lower the heart rate. You can’t squint with your ears.

Once the heart rate got over 175, hearing diminished. The researchers concluded the blood rushing through the eardrums at that speed actually creates noise that cancels out what the person is hearing. That noise may come off as static, a hiss, or ringing in the ears. Hmmm… do firefighters and emergency responders working under stress ever experience heart rates above 175? You know they do. If your hearing is diminished due to a rapid heart rate, there is nothing you can do to rectify the situation other than lower the heart rate. You can’t squint with your ears.

Tune it out

The brain, in an effort to help you make sense of what is happening in a high-stress, high-consequence situation, can also filter out what it perceives to be noise – those sounds your brain determines to be unimportant. Sometimes this can be helpful. Other times it can be devastating. While full of Darwinian good intentions, the brain may filter out the sounds of the very thing that could kill you.

Sensory integration

What happens when the brain tries to sort out conflicting information? In other words, what the eyes are seeing and what the ears are hearing do not align (non-congruent). In this case the brain does its darnedest to make it all fit together in a coherent way. If you’ve ever been to a movie theater, you’ve experienced sensory integration. If you’ve never been to a movie theater, turn off your computer RIGHT NOW… and go see a movie.

In the movie theater the speakers are not behind the screen. They are on the walls. When someone on the screen is talking, the speaker is not where their mouth is. Yet it appears as though the sounds are coming out of their mouth. This is because the brain takes the cues from the eyes and the cues from the ears and integrates them… fits them together in a way you’ll understand and gives you the appearance the sounds are coming from the mouth on the screen… which they aren’t.

McGurk Effect

What you see overrides what you hear. It’s called the McGurk Effect and you are vulnerable to its consequences. Doubting me? Watch this video and doubt no more.

Vision trumps all

When there is a conflict between what the ears are hearing and what the eyes are seeing, vision will be the winner. This is why the sounds appear to be coming from the star on the movie screen, even though they’re not. A very simple, albeit perhaps juvenile, exercise can be used to test this phenomenon on an unsuspecting person. Tell the person to “Touch your finger to your nose” while actually touching your finger to your ear. Chances are very good they’re going to touch their ear, despite your verbal instruction to touch their nose. The brain takes its instructions from the eyes, not the ears.

On an emergency scene this can have some critical implications. For example, if you hear one thing on the radio yet see something else with your eyes, there’s a risk that in the process of sensory integration, your visual cortex wins and what you see is what is processed. The audible message, in turn, loses (is changed, distorted, or tuned out). It’s almost like the visual image convinces the brain to disregard the audible message because it doesn’t make sense. As you can imagine, this can wreak havoc on your ability to develop and maintain situational awareness.

About the Author

Richard B. Gasaway, PhD, CSP is widely considered a trusted authority on human factors, situational awareness and the high-risk decision making processes used in high-stress, high consequence work environments. He served 33 years on the front lines as a firefighter, EMT-Paramedic, company officer, training officer, fire chief and emergency incident commander. His doctoral research included the study of cognitive neuroscience to understand how human factors flaw situational awareness and impact high-risk decision making.

_____________________________________________________

If you are interested in taking your understanding of situational awareness and high-risk decision making to a higher level, check out the Situational Awareness Matters Online Academy.

CLICK HERE for details, enrollment options and pricing.

__________________________________

Share your comments on this article in the “Leave a Reply” box below. If you want to send me incident pictures, videos or have an idea you’d like me to research and write about, contact me. I really enjoy getting feedback and supportive messages from fellow first responders. It gives me the energy to work harder for you.

Let’s Get connected

Facebook: SAMatters

LinkedIn: Rich Gasaway

LinkedIn: Situational Awareness Matters

Twitter: Rich Gasaway

Youtube: SAMattersTV

itunes: SAMatters Radio

Stitcher Radio: SAMatters Radio

Google Play: SAMatters Radio

iHeart Radio: SAMatters Radio

It’s times like this that the black out masks come in pretty handy. You are forced to use your ears not only to hear what’s going on around you but to “see” it as well. A lot of the time when I am in a black out situation, when I hear things around me I can create a picture of what may be going on. There would be times during training with the black out masks, the training officers would keep telling us to stop for a few seconds, hold your breath to block out the sound of the air pack, and then ask what direction is the apparatus outside the building or which direction do you hear the traffic passing outside so as to help get your orientation and create that mental picture of where to go. Many is the time also when you are IC at a scene, the crews inside are telling you that they see nothing or very little, but outside the fire just vented through the roof. As IC you know it is time to change the action plan and call for everyone out of the structure. Like you said, the crew inside gets confused and tells you they see nothing and want to ignore what you say, but you know better because you see what they don’t. Great topic, Rich, definitely something that needs to be addressed.

James Newman

District Chief 604-A

St. George Fire Protection District

14141 Airline Hwy.

Building 1 Suite H

Baton Rouge, La. 70817

jgnewman@stgeorgefire.com

http://www.stgeorgefire.com

http://www.sgpfa.org

Great research and point. Maybe the only way to live with the fact these impacts will and do occur, is to immerse ourselves in training. Loading up on our experiences where situational awareness is critical.

Robert,

Loading experiences is part of the solution, for sure. So long as the experiences are realistic and repetitive it will help develop skills that will be automatic performance under stress. Thanks for contributing!

Rich

Pingback: Stress: The Nemesis of Situational Awareness | Situational Awareness Matters!™

Pingback: Explanations for Situational Awareness Insanity-Part 3 | Situational Awareness Matters!™Situational Awareness Matters!™

Pingback: Stress: The Nemesis of Situational Awareness | Situational Awareness Matters

Pingback: Lawyer: Officer Who Shot Terence Crutcher Was Unaware She Had Backup – Bearing Arms

Pingback: What Your Body Knows – Active Threat Response Training

Pingback: Helping First Responders Overcome the Effects of Stress | Field Office America

Pingback: Responding to School Shootings: Addressing Police Officer Trauma | Field Office America

Pingback: A former police officer’s viewpoint - Legal Regulation Review